We now come to the second plaque by the inner doors, and there see an important personage from the church's past.

This is the man who was in charge of the building of St. Clare. From what I have been told of the time, he probably had a great hand in the design of the church. The priests were apparently allowed to chose either from a series of designs put forward by the diocese, or they were allowed to seek out architects and begin designs to their specifications. Priests of that era, I am told, often tried to get the architects to design churches like ones they knew elsewhere, or had seen in their travels.

Now, had I been a priest of that era, the urge to abuse such power, if the stories are true, would have been near irresistible. I would have found an architect and said: "Okay, now there was this church I saw when I was in Rome that I really liked. It went by the name of 'St. Peter's'...."

The design Fr. McCabe chose was quite traditional and elegant. You can see this in the next picture, which gives you an idea of the view from the inner doors, looking down to the altar:

Traditional designs such as this have their roots in the Medieval times. At that time, the Church leaders designed the churches themselves to teach the faithful something about their faith and the stories of the Bible. They used methods like this to teach because the overwhelming majority of the faithful could not read. So they turned their churches themselves into tools for telling tales, and for reminding the people of the things they should know.

Tied into this is an ancient mnemonic device- one which is still regarded as the best memory trick around- which the people of the middle ages honed to near perfection. It is called "memory theatre", and its premise is simple: you create a building in your mind, and you fill it with little objects that will jog you memory. Whenever you wish to remember something, you walk through the mental building, and see the object you wish to remember. The building most commonly used for this trick was a church.

Building themselves were designed to remind and teach us of our faith. The common cruciform floor plan (which St. Clare's has) is one such example of how the building itself embodies the symbols of our faith. Another example: In the picture above you see the pillars supporting St. Clare's roof. There are twelve pillars in all. And just as there are twelve pillars supporting this physical church, so there are twelve pillars supporting the metaphysical Church, and those twelve pillars are the twelve apostles. To help drive home this connection, at the top of each pillar at St. Clare's is a medallion bearing a symbol of the apostles. Here are a few:

This is the symbol of St. John, the beloved. The chalice became his symbol from the words of Christ: "You shall surely drink of the cup I drink." Sometimes the chalice is pictured with a snake coming out of it. This is from a later story of John, in which someone attempted to poison a drink of his, but he blessed the cup before drinking, and the poison left his drink in the form of a snake.

This carpenter square is the symbol of St. Thomas, and it too comes from later traditions. According to this story, St. Thomas went into the east- perhaps as far as India, where he built a church- hence the carpenter's square. This is a legend you can really see the middle ages picking up and running with. You see, as an apostle, Thomas was a bishop in the eyes of the Church, and as a bishop, if he built a church then it wouldn't be just a church, but a cathedral. And what a cathedral it must have been! The medieval person would look at the cathedrals of his land and think, could an apostle have built anything less? No, not less, but greater!

This rather dim one is the symbol of St. Paul. He is included because, well, frankly, Judas is not considered a pillar of our Church. Saint Matthias, whom the Apostles elected to replace Judas is not represented, in stead Saint Paul makes up the 12th pillar. St. Paul's symbol is a book with a sword. The book symbolizes the letters of Paul, and the sword the instrument of his death. Instruments of death are common among the symbols of the apostles. There is also Andrew's transverse cross, and Bartholomew's knife (he was flayed and is often portrayed holding his own skin) and James' club.

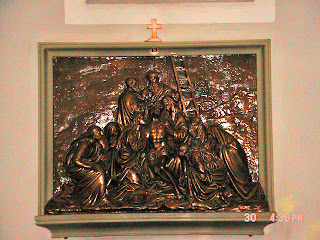

Other symbols are common to all churches, or should be, such as the stations of the cross. St. Clare's is fortunate to have beautiful ones. And not only are they beautiful, you can easily tell what they are.

(Jesus is taken down from the cross).

Everything in the church can be used to tell the stories or teach people, including the stained glass. In the medieval churches, the more symbols you could crowd in, the better. St Clare's doesn't go that far, yet it has many stories and symbols built into it. For instance, has ten stained glass windows depicting the Joyful and Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary. Here are a few photos that turned out better than the others (click for larger size):

And if there is any doubt as to whom this church was dedicated, there are two windows over the altar of St Clare. Like the other symbols I have discussed, the windows are dynamic: they are not intended to be a static picture but rather a reminder of a whole story. The window on the right shows Clare with her ciborium:

(click to enlarge)

Before her are the Saracen mercenaries, crouching in fear before the True Body, and preparing to flee. It is a picture worth the proverbial thousand words.

Statues were also used to tell stories, providing you knew the symbolism. For example, meet this gentleman:

He is known variously as St. Rocco, or St Roche, and everything you need to know about him is shown to you here in this statue. Remember that for the Middle Ages it was not important to show what a person looked like, but rather to show what they were, preferably from the perspective of heaven.

We can see instantly, for instance, that this man was holy and Christ-like in his life. And how can a sculptor make a statue that shows a man to be Christ-like? you may well ask. Well, by giving him a head like this:

We can see instantly, for instance, that this man was holy and Christ-like in his life. And how can a sculptor make a statue that shows a man to be Christ-like? you may well ask. Well, by giving him a head like this:

We have no idea what Rocco actually looked like, but to the middle ages the physical appearance was unimportant. It was the spiritual reality they sought to depict. Hence, they gave Rocco the features of Christ, not because he looked like Christ but because he lived Christ's teachings.

show him to be a pilgrim. He points to the sore on his thigh

which tells you he is connected to the Black Plague, as this- it's called a Bubae, by the way, which is where the name Bubonic plague comes from- was one of its symptoms. Dogs such as this one

are often used to represent fidelity and faithfulness, but not in this case. This is a dog from his story (Note the bread in its mouth, it is important for later), and Rocco's story goes like this:

Rocco was a pilgrim travelling to Rome during the time of the Black Death. During his travels he passed through many villages where people were suffering from the dreaded disease. Unlike most travellers, who shunned the sick out of fear of catching the disease too, Rocco paused in his travels and treated the sick as best he could. He helped many people until one day he saw the swelling on his thigh and realized that he now had the disease. Unwilling to he a burden on anyone, he went into a cave to die. While in the cave, a friendly dog found him, and the dog, realizing Rocco's plight, began bringing Rocco food. The dog's owner, wondering where his dog was going with the food, followed the dog to the cave and found Rocco there. The owner brought Rocco home and treated him. Rocco recovered, and in time completed his journey to Rome. He is now the patron, among other things, of sufferers of the bubonic plague.

If you ever want to remember his story, just think of this statue, and the rest will come to you.

I will pause here again for the night. Puff wants to use the computer. I'll continue more tomorrow night.

God bless.

1 comment:

Of course this was my parish for like over 30 years. It is the church where It is the church where I made my first confession in the late 60's and sang in the choir in the early 80's.

For a long time; I never understood the original altar at the back below the painting was an original altar; never having seen a priest not facing the people.

It is a beautiful church and it's great that they are maintaining it and restoring it.

Post a Comment